A 1950s woman was, Franklin writes, “pressured by the media and the commercial culture to deny her personal and intellectual interests and subsume her identity into her husband’s”, and Jackson’s fictional exploration of this conflict, she argues, “constitutes nothing less than the secret history of American women of her era”. It was a time of rigid and rigidly enforced gender roles, as many women struggled to reconcile their own ambitions with society’s expectations. In Jackson’s work the house of fiction is always a haunted one, and usually it is women who are being disturbed, in both senses of the phrase.įranklin situates Jackson’s conflicted relationship with coercive postwar US domesticity within the context that would give rise in 1963 to Betty Friedan’s attack on “the feminine mystique”. “The relationship between a person’s surroundings and his or her mental state was one she understood well,” Franklin somewhat understatedly observes. We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Jackson’s final novel, brings social and psychological demons together in an unforgettable gothic space. (She pretended to be a witch, and was once labelled “Virginia Werewoolf”.) The demons in Jackson’s fiction might be social, as in “The Lottery” or they might be personal and psychological, as in The Haunting of Hill House, which writers including Stephen King and Joyce Carol Oates have hailed as one of the greatest ghost stories of the 20th century. Jackson’s lifelong interest in rituals, witchcraft, charms and hexes were, Franklin convincingly maintains, metaphors for exploring power and disempowerment.

“The Lottery”, a simple tale of villagers fulfilling a summer ritual that ends with one of the most shocking twists in modern fiction, became an instant sensation, catapulting its author into literary celebrity.

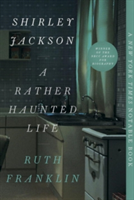

In 1948 the 31-year-old Jackson, who had been publishing magazine fiction for a decade without attracting much notice, produced a very brief story for the New Yorker that would change everything. “O ne who raises demons,” the writer Shirley Jackson once observed, “must deal with them.” Whether fiction could raise demons and deal with them remained for her an open question, one that drives Ruth Franklin’s comprehensive new biography.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)